1. Welcome

Welcome to the Archaeological Museum of Medina Sidonia, inaugurated in 2013. A museum that integrates several archaeological spaces and exhibition halls in its route, where the remains of the different civilizations that have passed through Medina Sidonia are exhibited.

Thanks to the initiative of the Town Council, the collaboration of many residents, archaeology professionals and the tireless work of Salvador Montañés Caballero in the field and the museography, we have been able to have archaeological collections of great interest and importance, part of which is exhibited in the rooms of this museum.

We hope you enjoy your visit and our 3,000 years of history.

2. First stop on the tour

In this first space we find what was once part of the Roman city called Asido Caesarina, which reached great urban splendor: in the 1st century an ex novo city was designed, in other words, all the previous urban space was leveled and new streets and squares were laid out, as well as the spaces in which the new public and private buildings were to be constructed. Although adapted to the geography of this hill, an attempt was made to follow the orderly grid system, with two main streets running north-south and east-west, the cardo and decumanus maximus, respectively, and other secondary streets running parallel to both. They are paved with large stone slabs, and the sewage system runs underneath them. We are in one of these secondary streets, with remains of house facades still visible on both sides.

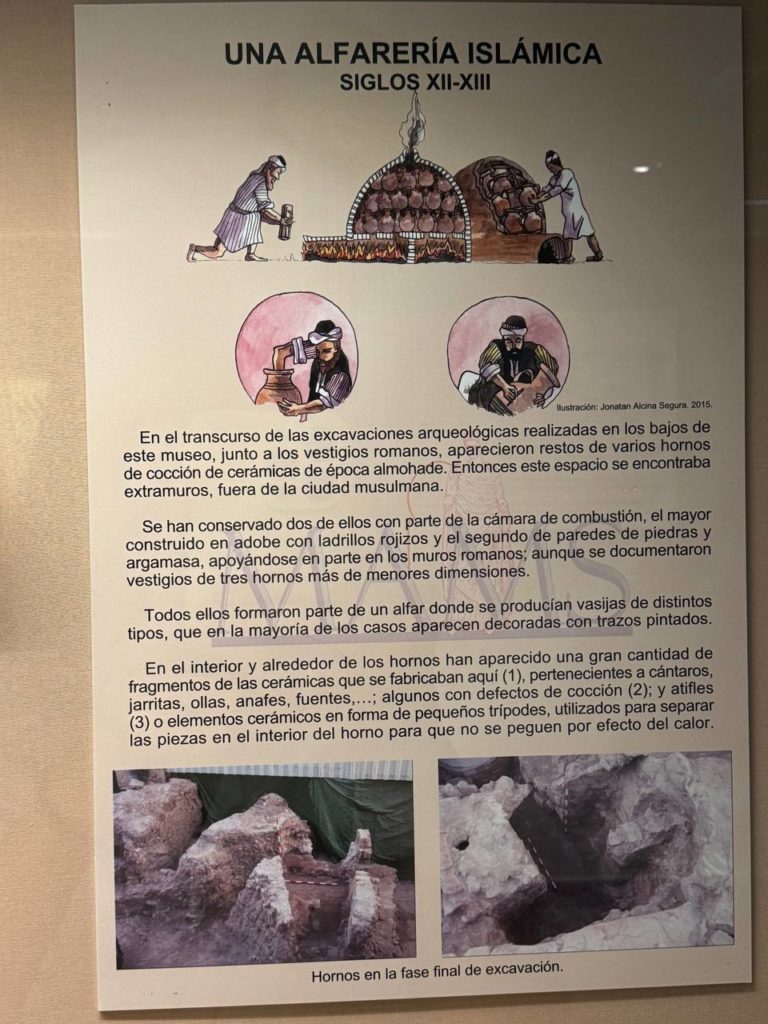

The only thing inside that doesn’t belong to the Roman period is the circular earthen and reddish brick shape that would have belonged to an Almohad-period kiln. This, the smaller one behind it and others that have not been preserved, formed part of a pottery industry in the last phase of the Islamic occupation of Medina Sidonia, which produced pots, jars and other vessels with painted decoration in many cases.

Three types of amphorae can be seen in the niches in this space, from right to left, amphorae for oil, wine and salted fish. Each container has a different typology, and a special shape, depending on the contents it stored.

3. Cryptoporticus

A cryptoporticus is a vaulted construction, sometimes underground or semi-subterranean. Its main function is to support a building or an open space above the vaults, and as a secondary use, its interior can be used for storage or stables.

In our case, the four cryptoporticos or vaulted structures, of which only one of them has survived in its entirety, fulfilled the mission of leveling the hillside terrain on which we find ourselves, thus allowing for a large and robust surface on which to build the main building that was raised above these vaults, which were the basements of the same.

The parts that are reconstructed with bricks belong to the refurbishment and conditioning of these spaces for visitors carried out in the first decade of the present century, as the original Roman work, from the 1st century AD, is made entirely of ashlars and sandstone slabs, with a rammed earth floor, which in some rooms is covered by channels that collect underground water and transfer it to the sewer in the neighboring street, preventing the cryptoporticus from becoming waterlogged.

4. The sewers

In addition to the one that runs under the paving of the street, you can walk through a section of the network of sewers that extends along the whole of Asido Caesaerina; there are more than 20 meters of underground hydraulic galleries that form part of the sewage system in Roman times, into which the dirty water and rainwater that was channeled out of the city flowed.

These sections of sewers were discovered in 1969 by a group of local youths, who were responsible for emptying them, as they were found to be clogged with earth; they would later fall into oblivion. It was not until 1991 when, on the initiative of the municipality and the Regional Ministry of Culture, they were investigated and restored.

The walls are made of sandstone ashlars and the vaults are half-barrel vaults. The original floor has been preserved, made with the waterproof mortar known as “opus signinum”, a mixture of crushed ceramic and lime. In the vaults and on one of the sides there are circular openings that connected directly with the buildings or the street above, which is where the water flowed into the sewer.

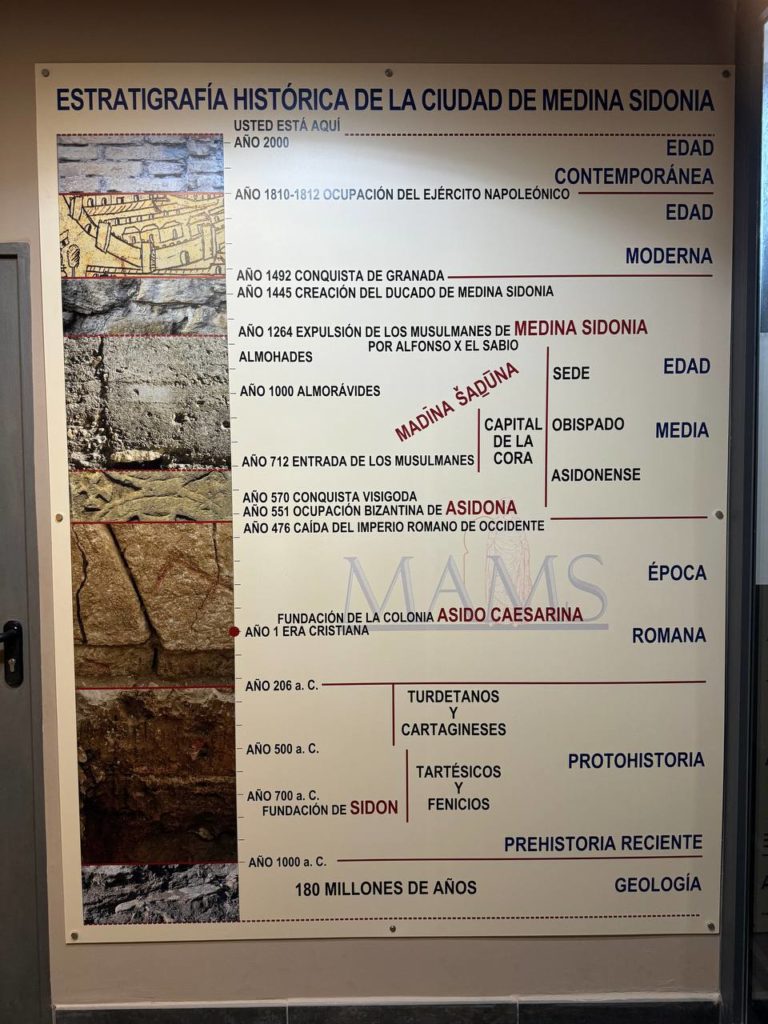

5. Stratigraphic panel

You are in front of the stratigraphic column which represents the evolution of the occupation of our town. The town of Medina Sidonia has some 3,000 years of history, as we informed you on your arrival at the Museum. According to tradition, it was founded by the Phoenicians, although they did so over an indigenous population that already existed on this hill, forming part of the mythical kingdom of Tartessos.

It can be seen how, throughout history, the place has had different names: Sidon or Punic Asido, Roman Asido Caesaerina, Visigothic Asidona, Islamic Madinat Saduna and Medina Sidonia since the conquest of Alfonso X.

Some highlights are marked, such as the seat of the bishopric of Asidon, the capital of the core of Saduna, the creation of the Duchy of Medina Sidonia in 1445, or the occupation by Napoleonic troops between 1810 and 1812, where the French troops maintained a garrison in the area of the Castle of Medina Sidonia.

6. Showcase 1

The pieces in this display case reflect different aspects of the daily life of the inhabitants of this hill during a long period of Recent Prehistory, and more specifically during what is known as the Metal Age. They are instruments made of stone, mainly with polished surfaces, a technique used for the manufacture of tools and weapons that developed from the Neolithic period onwards.

From these tools we know that their economy was based fundamentally on agriculture and livestock farming, clear examples being the axes and adzes for forestry work and tilling the land, the mills and crushers for processing the harvest, or the pieces of flint carved as sickle teeth for harvesting cereals.

The representations of idols carved in stone tell us about their religious beliefs.

Furthermore, the choice of this mountain as the site for their dwellings is not accidental, as it has the basic elements for living, such as an abundance of water, land for cultivation, for livestock and other immediate and nearby resources, as well as being a strategic location due to its ample visual control and easy defence.

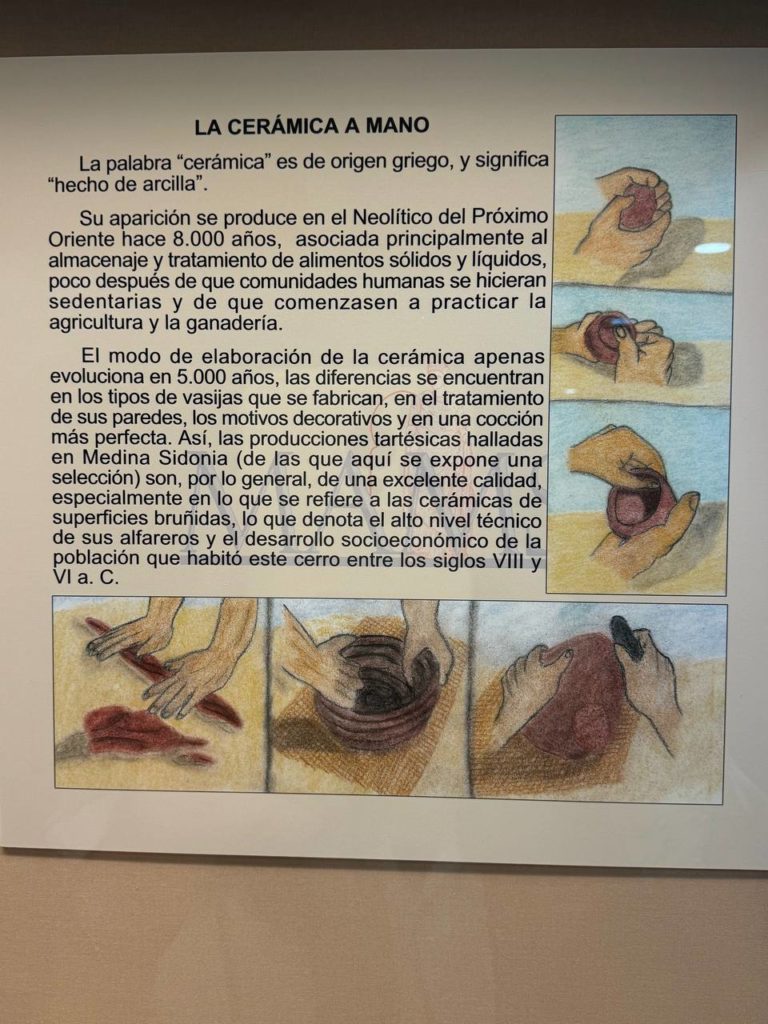

7. Showcase 2

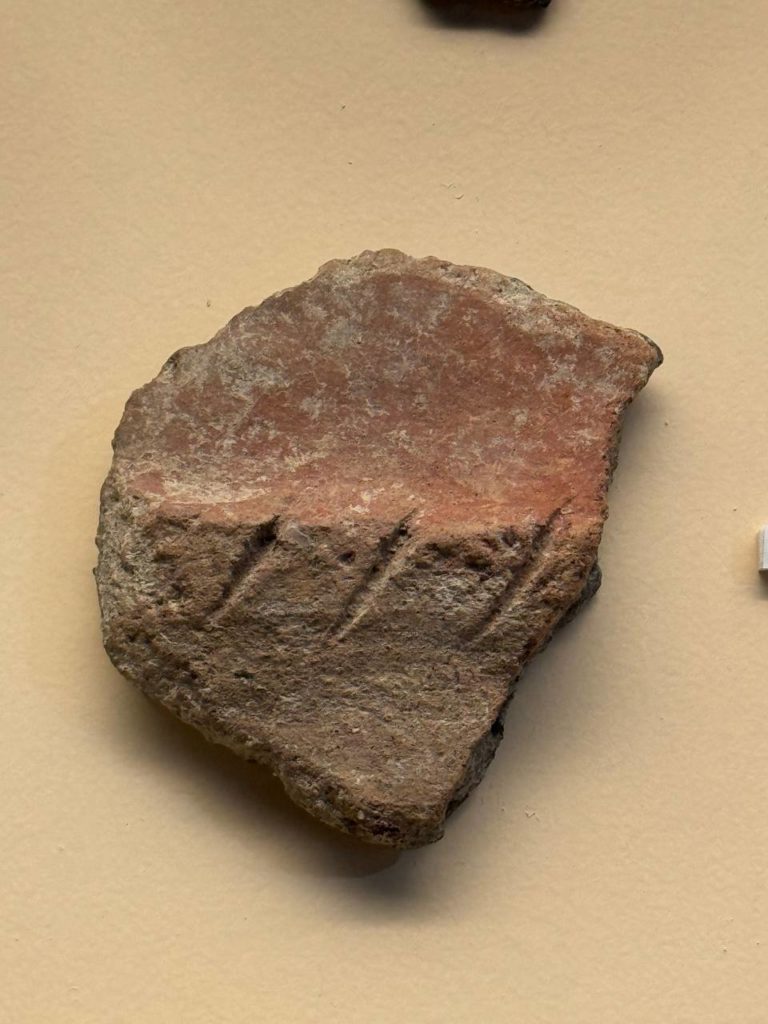

Although the ones shown here are not so old, as they belong to the Tartessian Late Bronze Age, the first ceramic artefacts appear in the Neolithic and are mainly composed of containers used for cooking or storing food and liquids; but although they are eminently practical objects, from the beginning they have also served as a support for artistic representations, their surfaces being treated with decorative or symbolic representations, either with reliefs, incisions, engravings or painting.

The word ‘pottery’, from the Greek ‘keramiké’, which translates as ‘the art of working clay’, has a double meaning. On the one hand, it indicates an inorganic, non-metallic material, very ductile in its natural state and rigid after drying and firing at high temperatures. On the other hand, it identifies the product itself with the material consolidated by the firing processes.

Before the invention of the potter’s wheel, pottery was made using various techniques, such as the churro technique, in which the walls of the vessel were created by successively assembling cylinders of clay and, once the desired height had been reached, smoothing the surfaces on the inside and outside, shaping the rim and applying handles if necessary; the same purpose was also achieved by hollowing and shaping a fresh lump of clay directly; or by joining sheets of clay together.

As a curiosity, three fragments corresponding to the base of different pots are shown, which have a geometric pattern printed on them, which was formed when the potter placed the fresh clay on the plaited vegetable mat on which he began to make the pot, so we should not consider it a decoration, but a chance occurrence.

The high degree of perfection of the ceramics with burnished surfaces denotes the high technical level of the potters and the socio-economic development of the people who inhabited the hill between the 8th and 6th centuries BC.

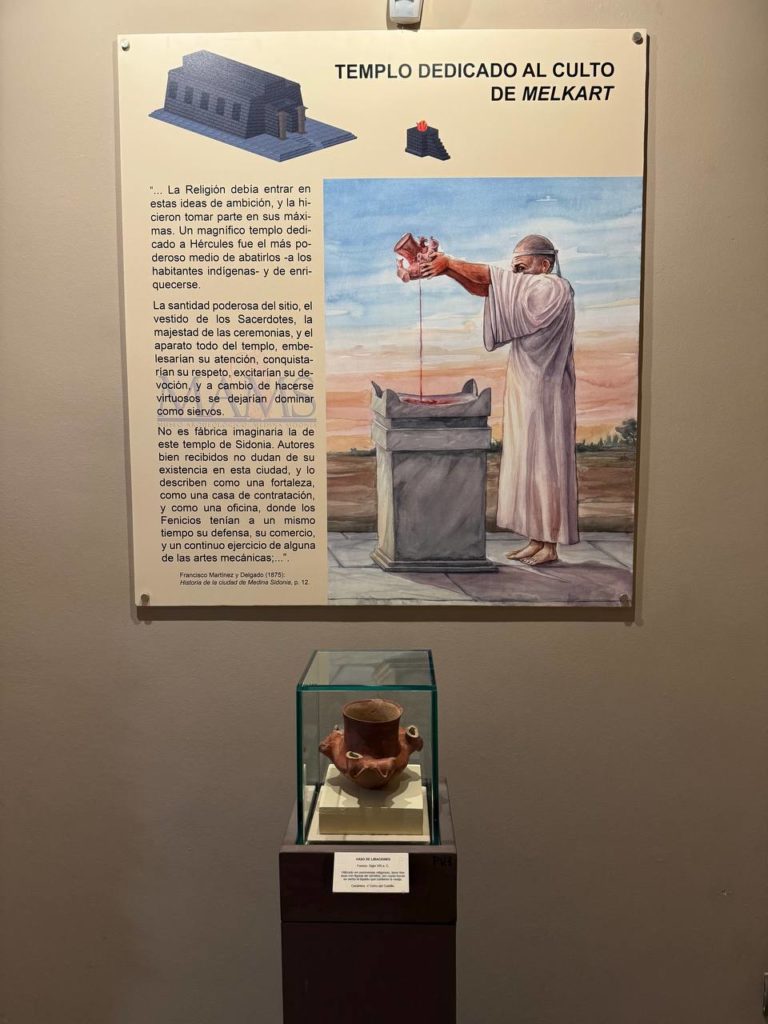

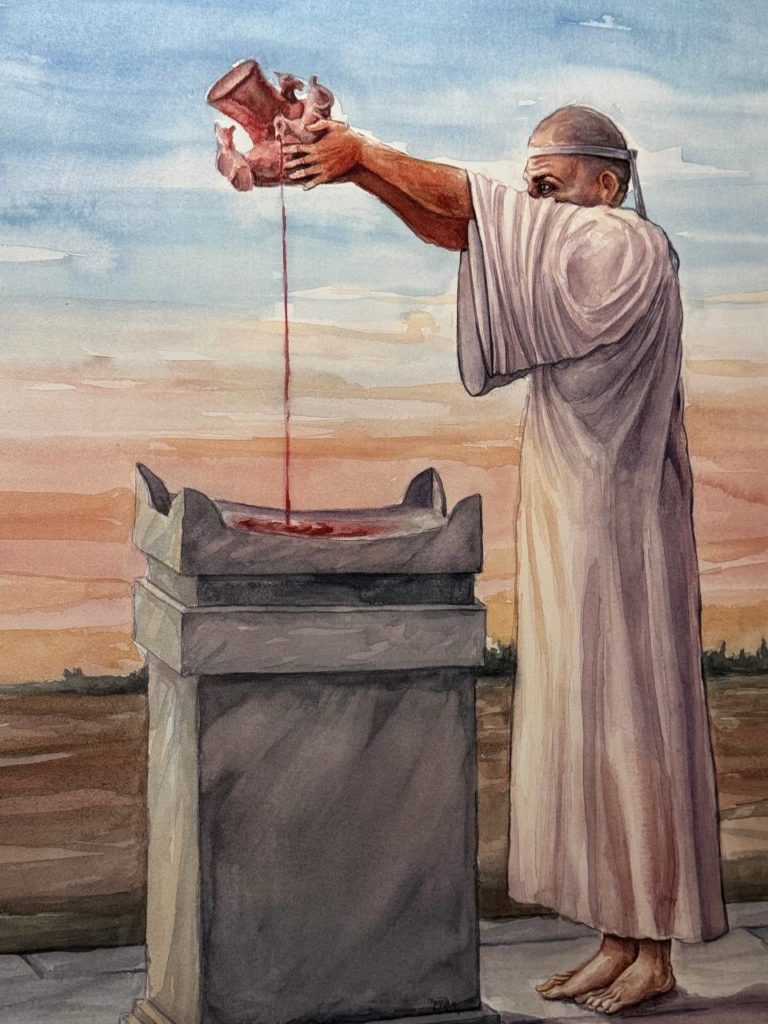

8. Libation vessel

This is one of the most significant pieces in the Museum. It is a Phoenician ritual vessel from the 8th century BC, used in religious ceremonies to make libations. It is a testimony to the passage of Phoenician culture through these lands, which ancient authors tell of in their accounts, stating that the Phoenicians from Sidon founded a settlement here on this altitude to engage in trade and exploit the resources of the surrounding area.

The vessel is a globular-bodied piece with a bell-shaped neck and rim, with three zoomorphic handles, with figures of crows lying down, through whose mouths the liquid contained inside the vessel was poured.

This piece can be related to the tradition also referred to by chroniclers of past centuries, who speak of the existence in Asydos of a temple dedicated to Melkart, a Phoenician divinity protector of trade and travel, assimilated to the Greek Herakles or Hercules of the Romans.

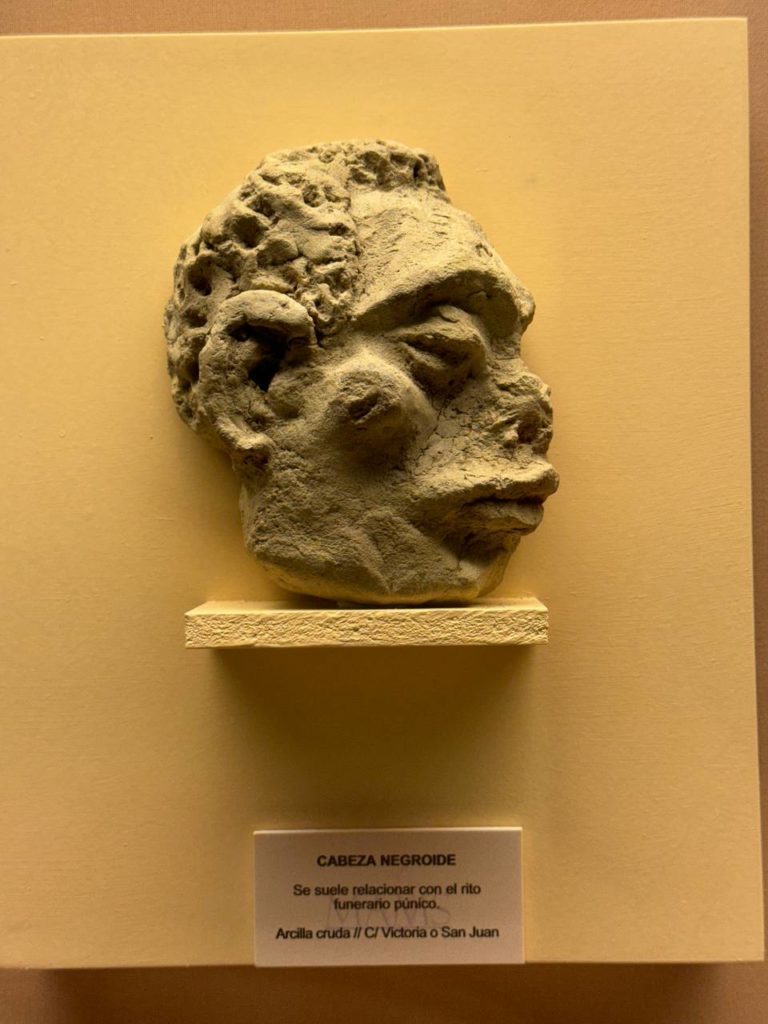

9. Showcase 3

Asido, before the conquest of these lands by the Romans in 206 BC, formed part of the group of cities known as Libyano-Phoenician, with a significant number of Punic inhabitants and other autochthonous inhabitants who assimilated the customs, religion and even the alphabet derived from Phoenician, maintaining a strategic military nucleus at this altitude that controlled a large territory, as well as being dedicated to the agricultural and livestock exploitation of the surrounding fields.

One of the most important pieces in this display case is the negroid mask used in funerary rituals to be placed as a trousseau next to the remains of the deceased, which has the particularity of being made of unfired clay.

Also of note is the set of weapons (spearhead and bronze knife and iron axe) found on the Cerro del Castillo hill next to a cremation, which must have belonged to a Turdetan warrior.

The painted ceramics typical of the Iberian world; and the remains of vessels and lucerne of Greek origin, examples of the commercial contacts with the eastern Mediterranean.

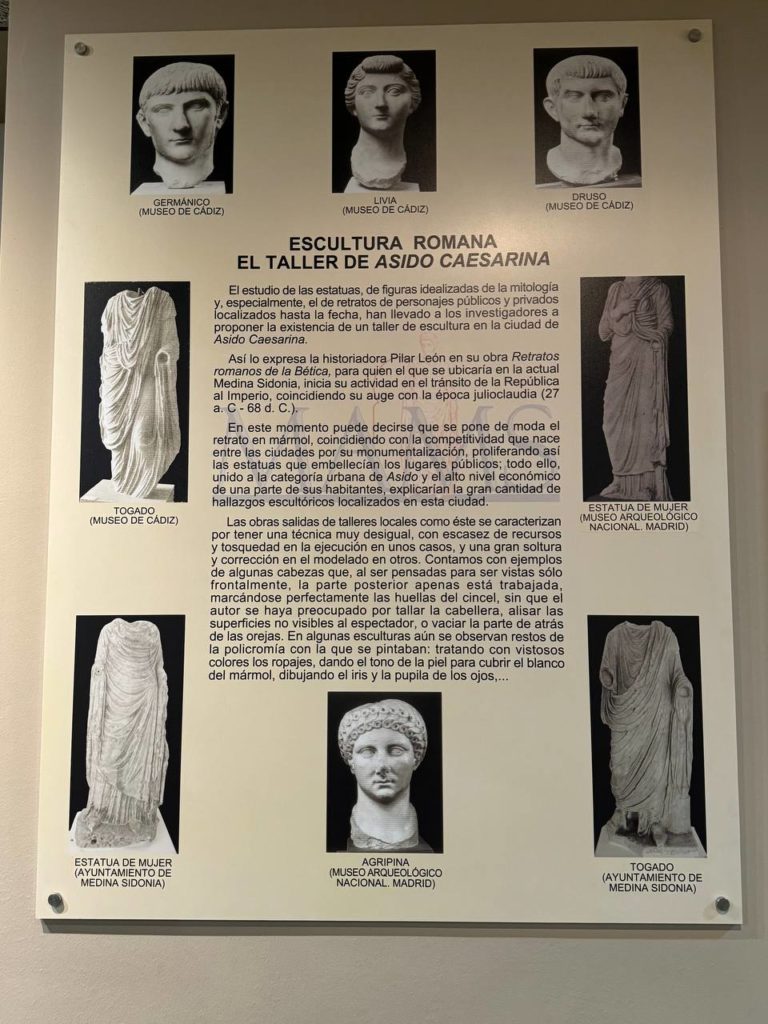

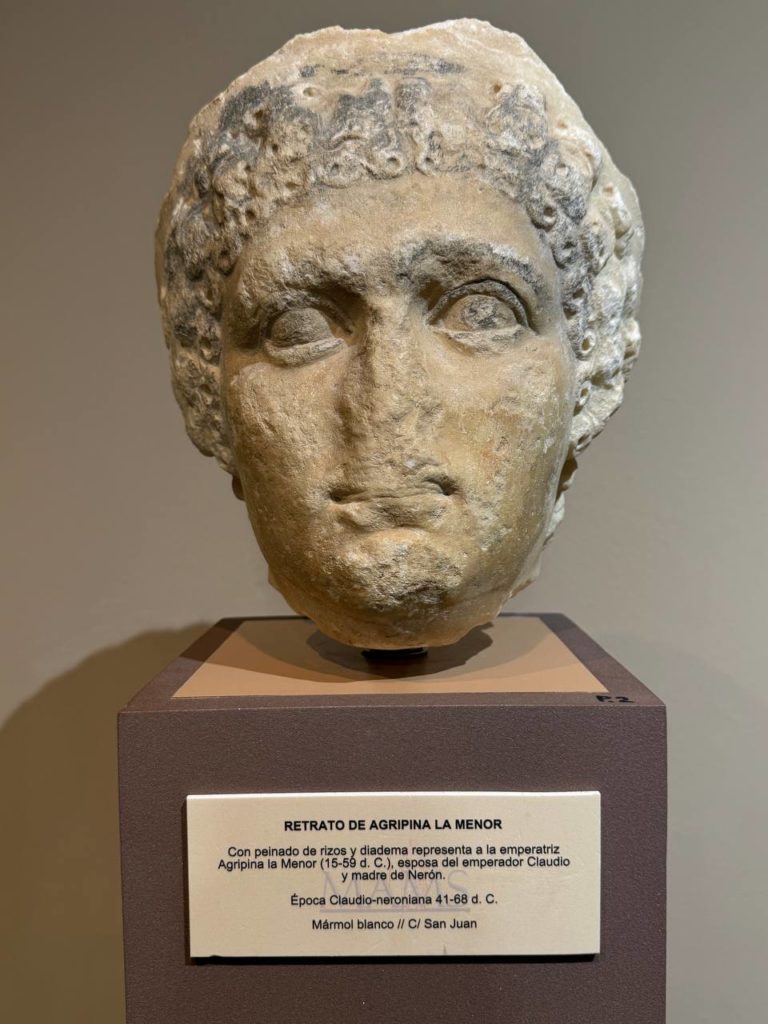

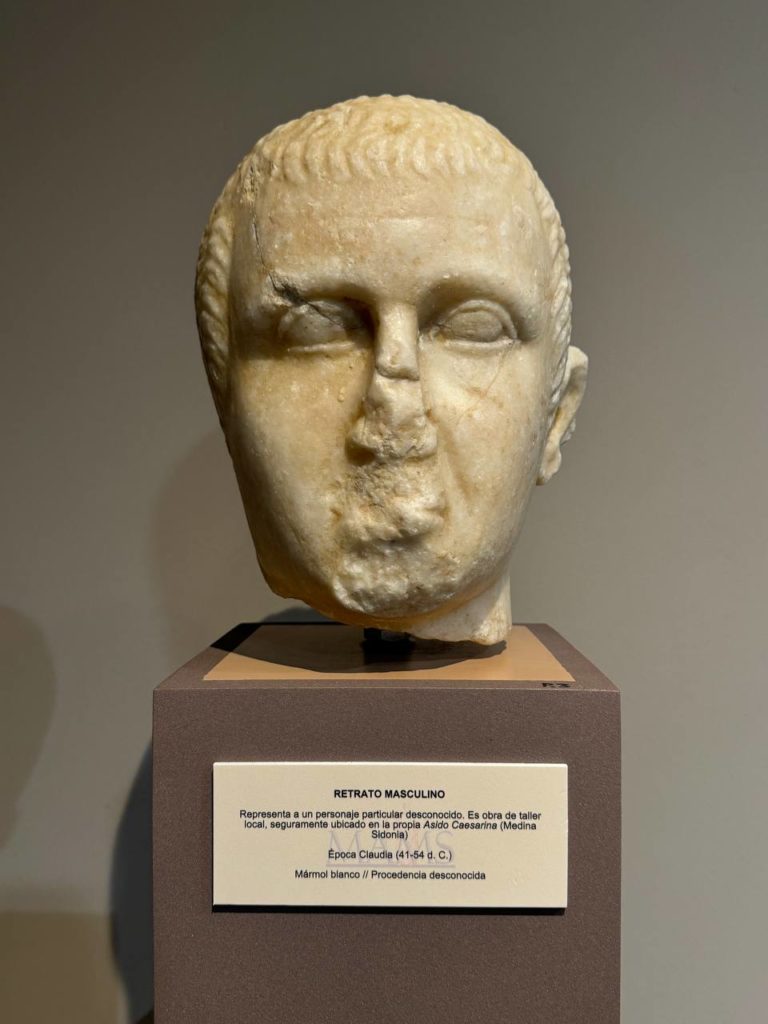

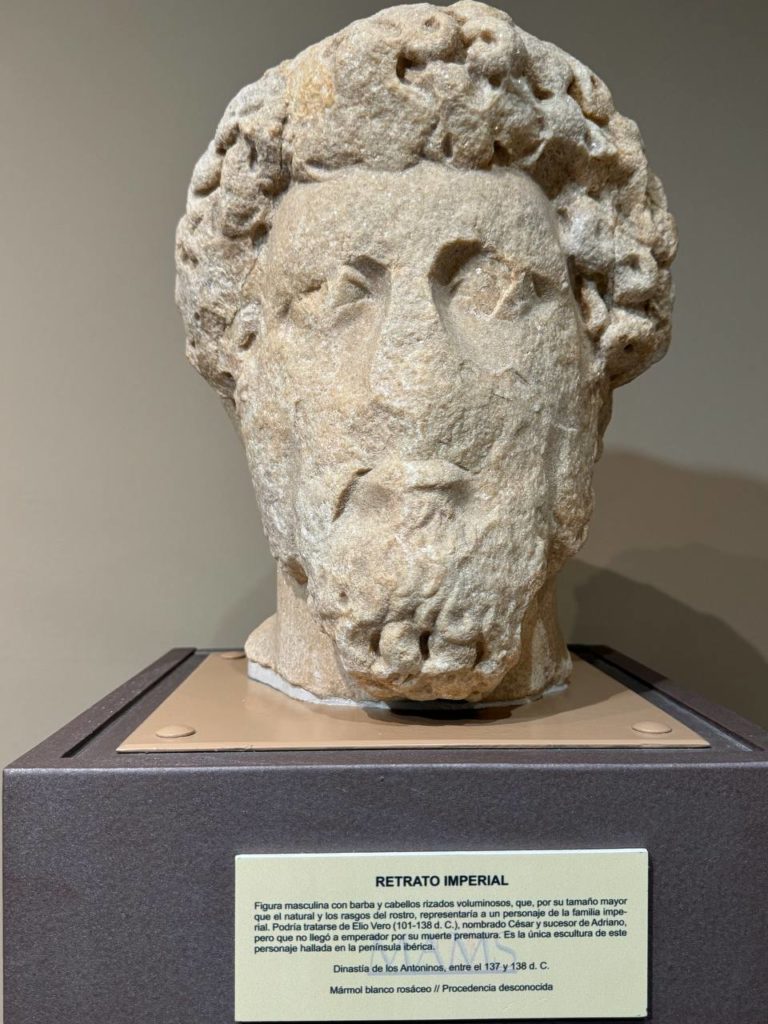

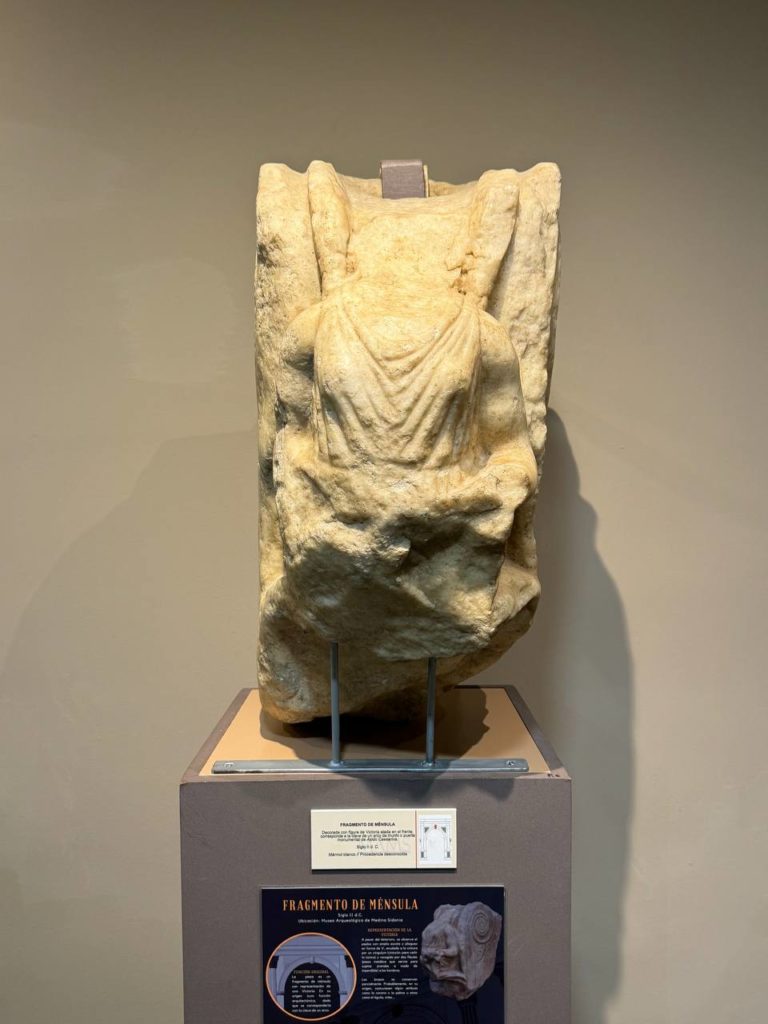

10. Sculpture

Researchers believe that there was a sculpture workshop at Asido Caesarina. Its activity would have taken place during the transition from the Republic to the Empire, coinciding with its peak in the Julio-Claudian period (27 BC-68 AD).

At this time there was a great production of marble sculptures and portraits, coinciding with the competition that arose between cities for the monumentalisation and embellishment of their buildings and public and private spaces. The urban status of Asido and the high economic status of some of its inhabitants would explain the large number of sculptural finds found in this city.

There are examples of some heads which, as they were intended to be seen only from the front, the back of the head is barely worked, with the marks of the chisel being perfectly marked, without the author having bothered to carve the hair, smooth the non-visible surfaces or hollow out the back of the ears. This shows that they are the work of a local workshop, whose sculptors know the technique, sometimes execute it with great skill, but do not waste time on detail work that is not very visible.

In some sculptures, part of the polychromy that covered them has survived, as in the bust of Agrippina the Younger, where black traces can be seen around the eyes and hair. This is an example of a representation of members of the imperial family; in other cases we find portraits of private individuals, images of gods or other figures from ancient mythology.

11.Roman building materials

The architectural and decorative elements of buildings that have been found by chance or in the different archaeological excavations carried out in the city, show that Asido Caesarina had a large number of powerful families, who in addition to contributing to the aggrandizement of their city, surrounded themselves in the private sphere with all the luxuries that were available to them at the time.

Column shafts, bases and capitals, cornices and decorated plaques, both in local sandstone and different marbles from all over the Mediterranean area, pieces of mosaics, pieces of opus sectile of finely worked stone slabs of different types, fragments of mural painting, etc., show us the grandeur of some public buildings and the wealth of many of the private domus.

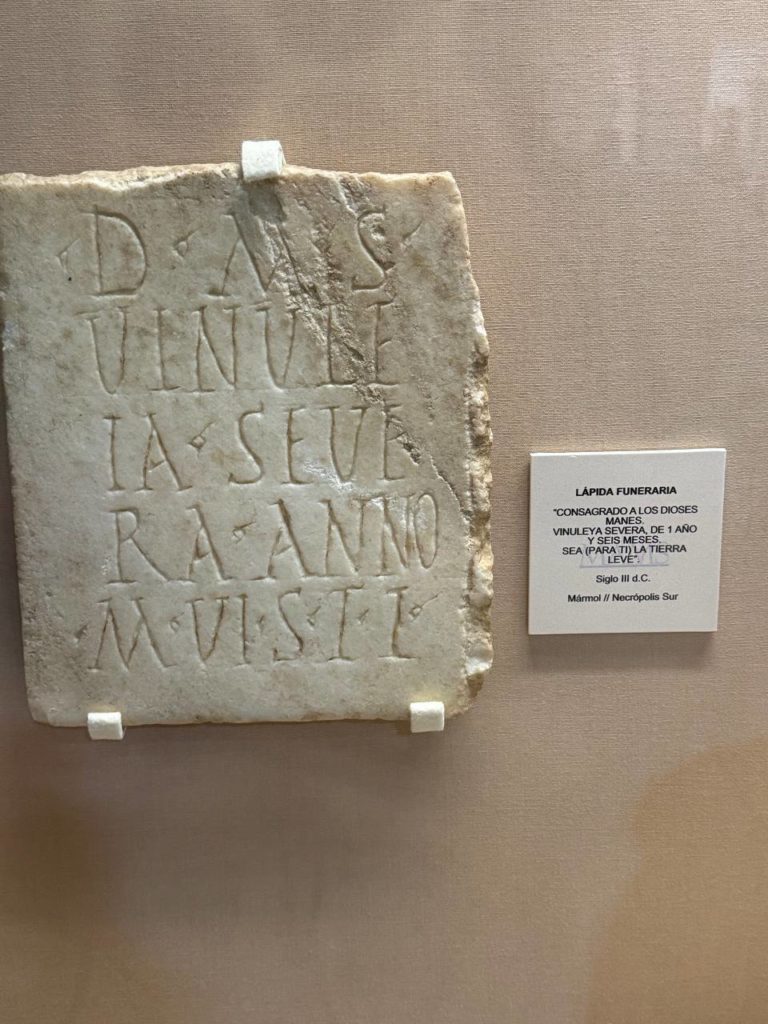

12. Roman funerary world

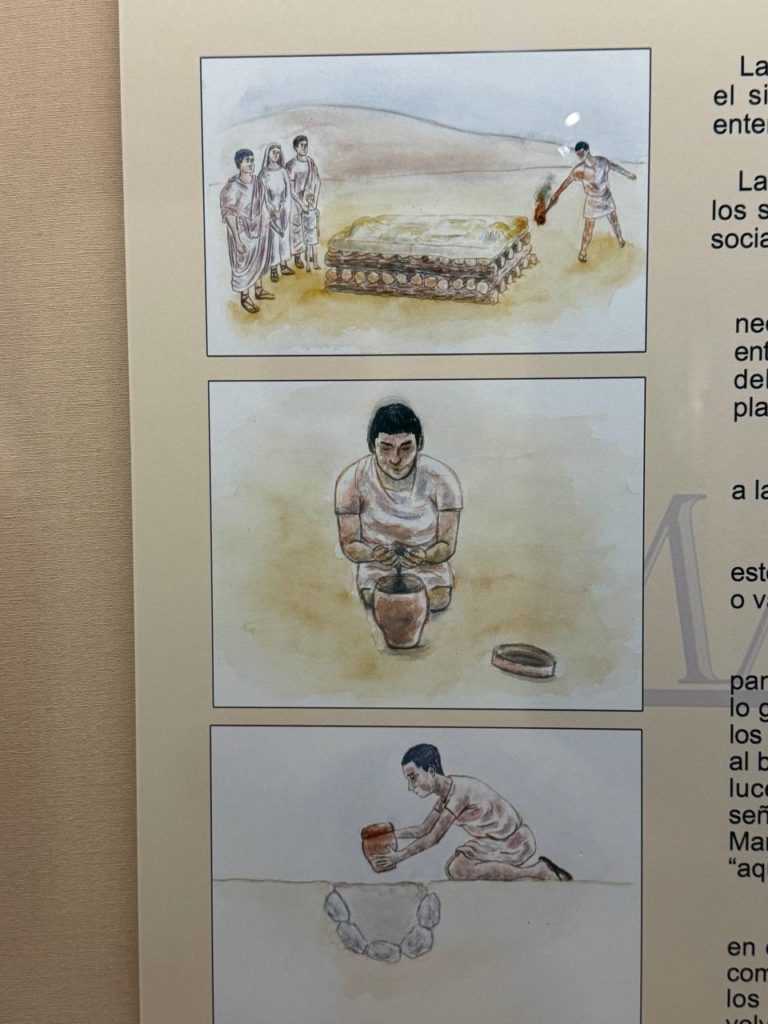

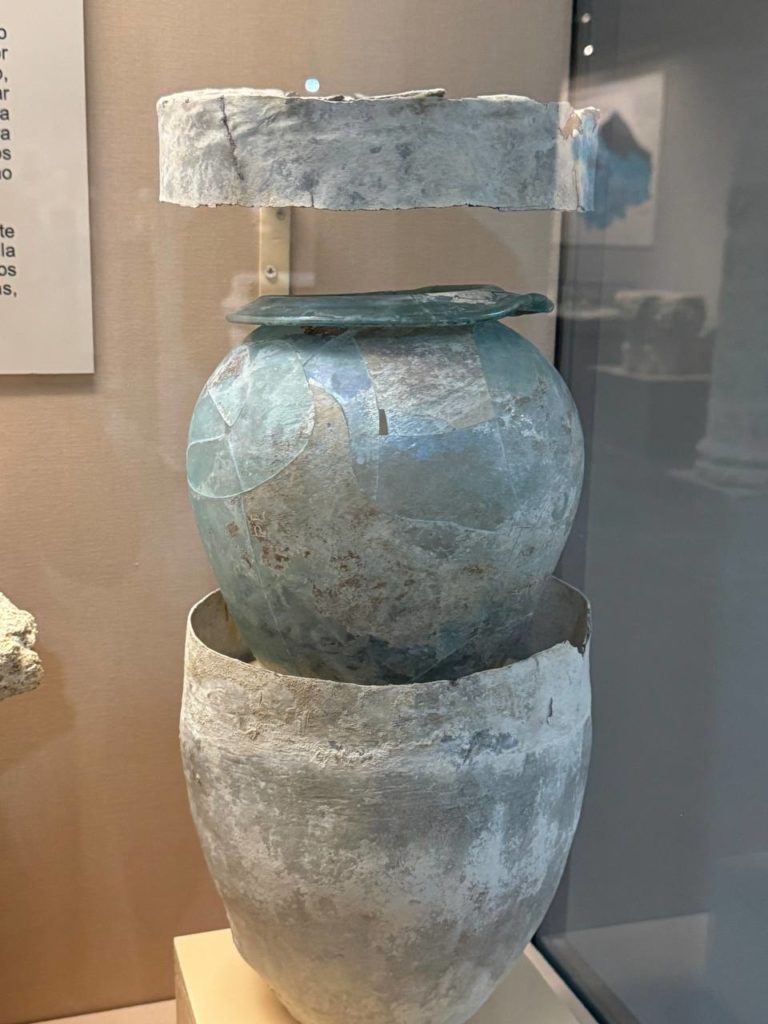

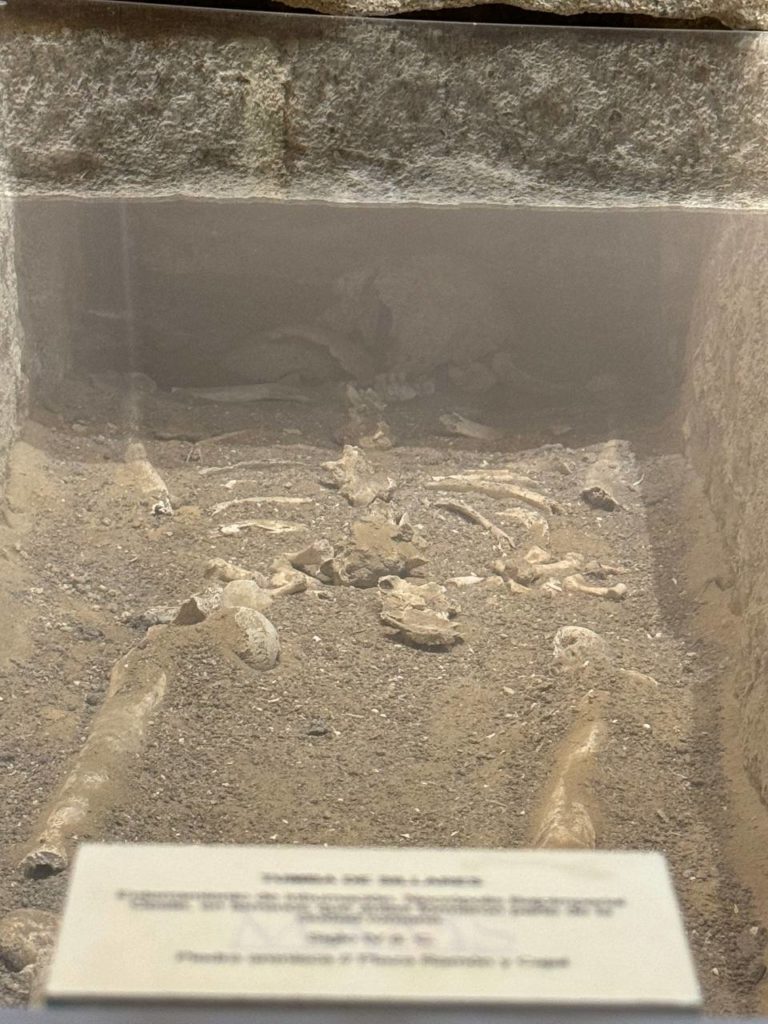

Through the pieces on display, we will now see how the Romans buried their dead, their rites and customs, which hardly changed over the centuries, and even today many of these customs are very familiar to us, as they have been maintained over the years.

The necropolises were located outside the city limits, next to the roads leading to them. It was to them that the deceased was taken once he or she had been watched over at home by relatives and friends, who formed a cortege, with musicians and mourners if the family economy could afford it. The ashes or bodies of the deceased were buried underground or placed in columbaria or family vaults. The grave was usually marked with a tombstone with the name of the deceased, their age and a phrase of affection. A ritual meal or banquet was held, where a part was reserved for the deceased, and in successive years the place was visited on special dates, leaving a gift. Mourning lasted for 10 months, a time of respect during which the widow or widower waited to remarry, and no personal adornment was flaunted, nor were parties held in the family’s closest circle.

There were two types of burial: cremation and inhumation. Cremation was the most widespread ritual during the Roman Republic and up to the 2nd century AD, and from then on burial became the most common burial custom, especially as Christianity gained in popularity.

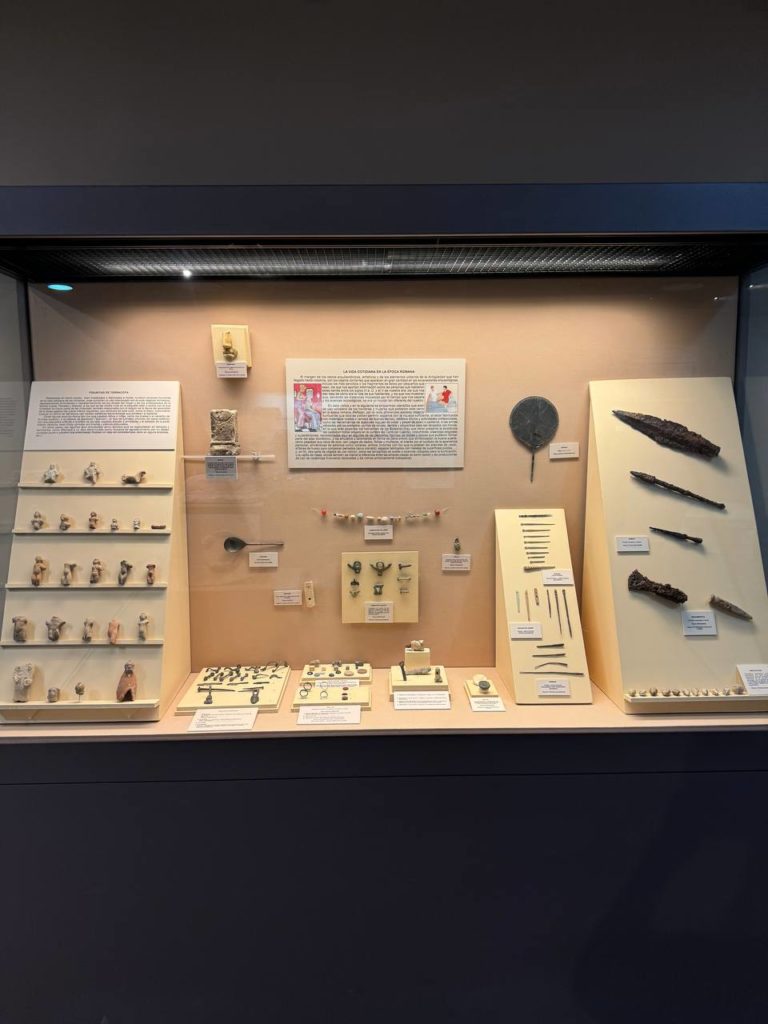

13. Showcase of everyday life

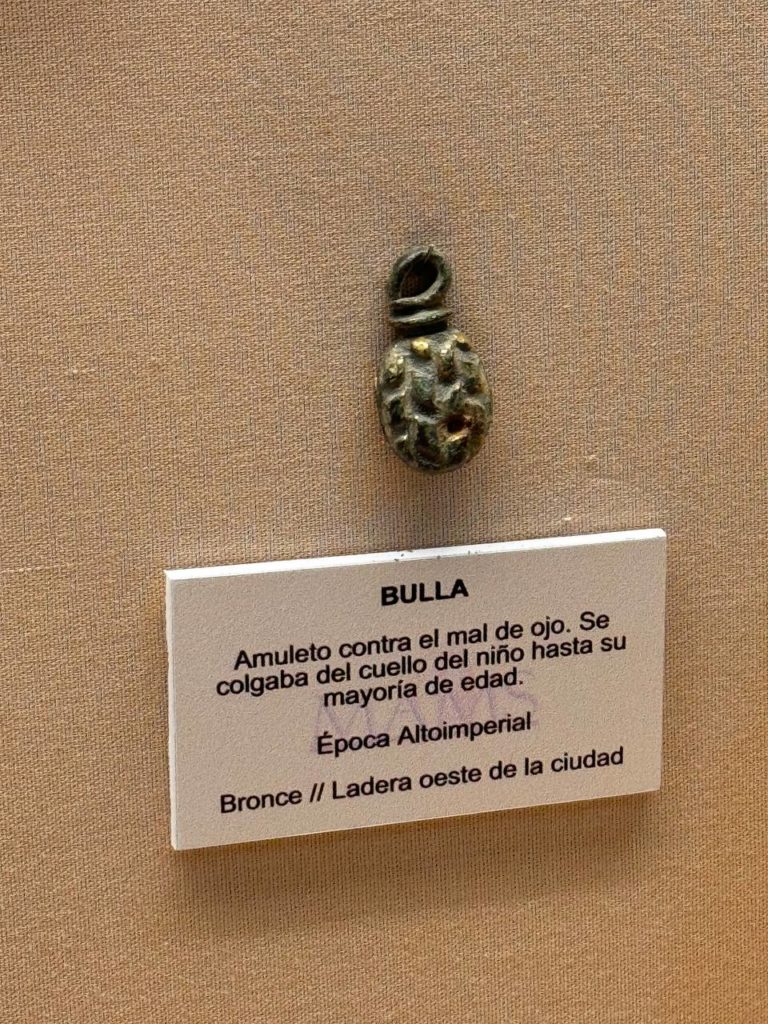

This is a showcase displaying various objects from everyday life in Roman times. Some of them are very similar to modern-day objects, such as necklaces of colored beads, which could be found in any accessories shop, rings, spoons, a mirror, etc.

The bulla is a curious object. It was a pendant or medallion which, as an amulet to protect the wearer from all evil, was hung around the neck of male children nine days after their birth, and was removed when they came of age.

Other amulets on display include phallic amulets. The phallus, which is associated with the power of fertility, fertility in nature and sexuality in general, as a personal amulet protected its owner against evil spirits and the evil eye.

It is not uncommon to find tokens made of different materials, dice and tabas in the excavations, as the Romans were very fond of games of chance; and this display case shows a good number of these pieces. And as a curious fact, although the shape of some of the dice is close to perfect cubes with 6 totally equal faces, some have been found that are visibly non-cubic, that is, asymmetrical or slanted, which favour certain rolls, especially the numbers 1 and 6. Were the Romans cheats at dice? Some certainly were.

14. Roman pottery

You have before you several fragments of terra sigillata vessels, a distinctly Roman type of pottery used as luxury tableware, characterized by the fact that many of them have the potter’s name or sigillum printed on the base of the piece. These ceramics are recognizable by their striking, more or less bright red color, and in many cases, their outer walls are decorated with geometric, figural or vegetal motifs. The chronology of these wares ranges from the 1st century BC to the middle of the 3rd century AD, although they may have been produced until the end of the empire with much lower quality.

There are other varieties with a black glaze, known as ‘Campanian ware’, which ceased to be produced with the change of era; or ‘marmorata’, whose walls resemble veined marble.

The pondera, in Latin, pondus, or loom weight, is a piece of pottery or stone that serves as a weight for tightening the warp threads of a loom. Loom weights are found in different shapes, sizes and materials.

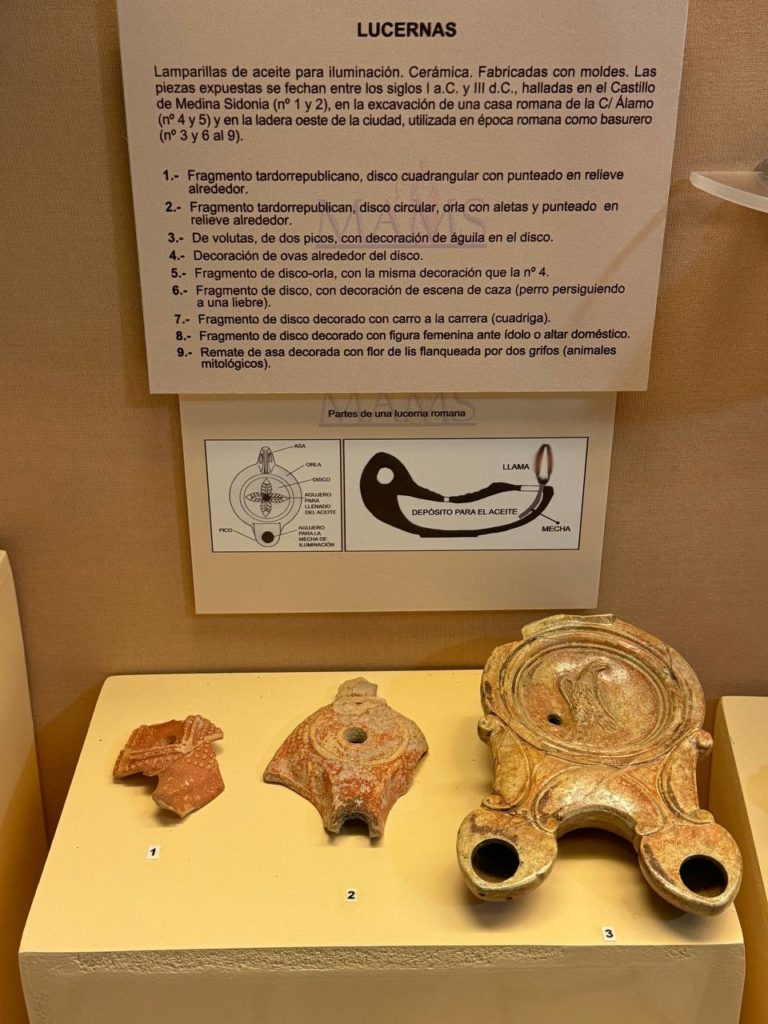

The “lucernas”, also represented in this display case in several different models, are the ancient Roman lamps used for illumination, usually made from clay in molds, although they were also made from metal. They were generally oval-shaped vessels, with a central disc that was usually decorated with a figure, plant element or group from everyday life or mythology, with a hole through which the oil was poured to serve as fuel for the inner tank; at one end there was a handle and at the other end a small projection or spout with a hole also connected to the tank, into which the wick was placed to light the flame.

The display case is completed by common pots and jugs and glass objects made with great skill, such as the “millefiori” bowl, made of multicoloured crystals reminiscent of the glass still produced in Venice today.

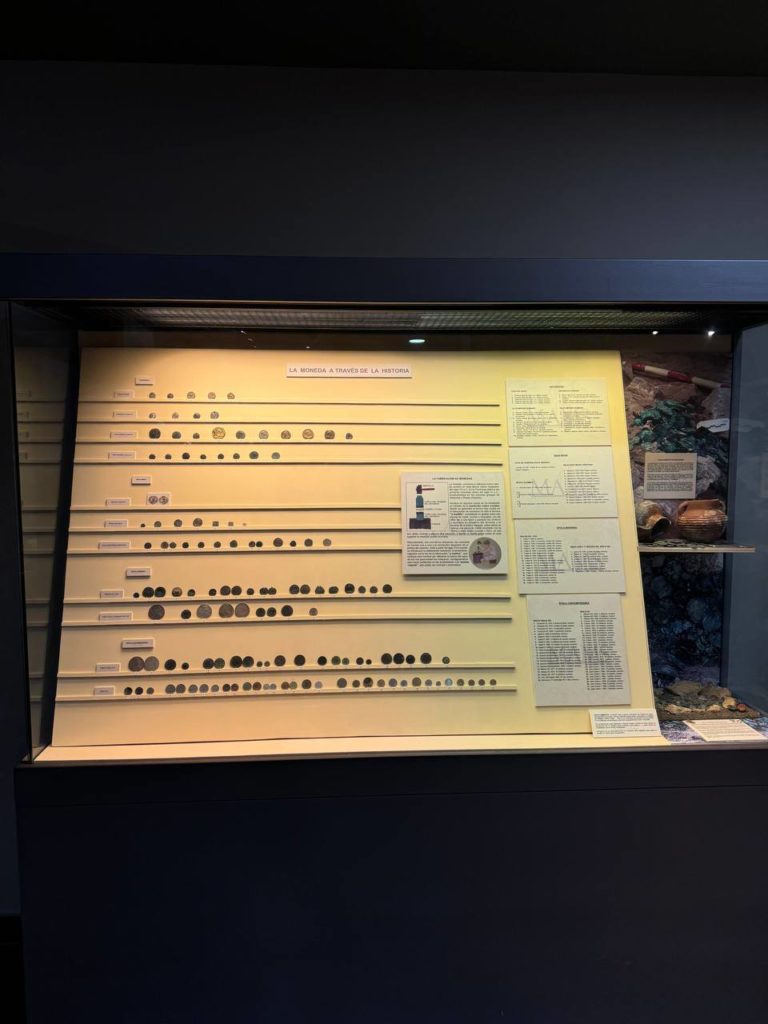

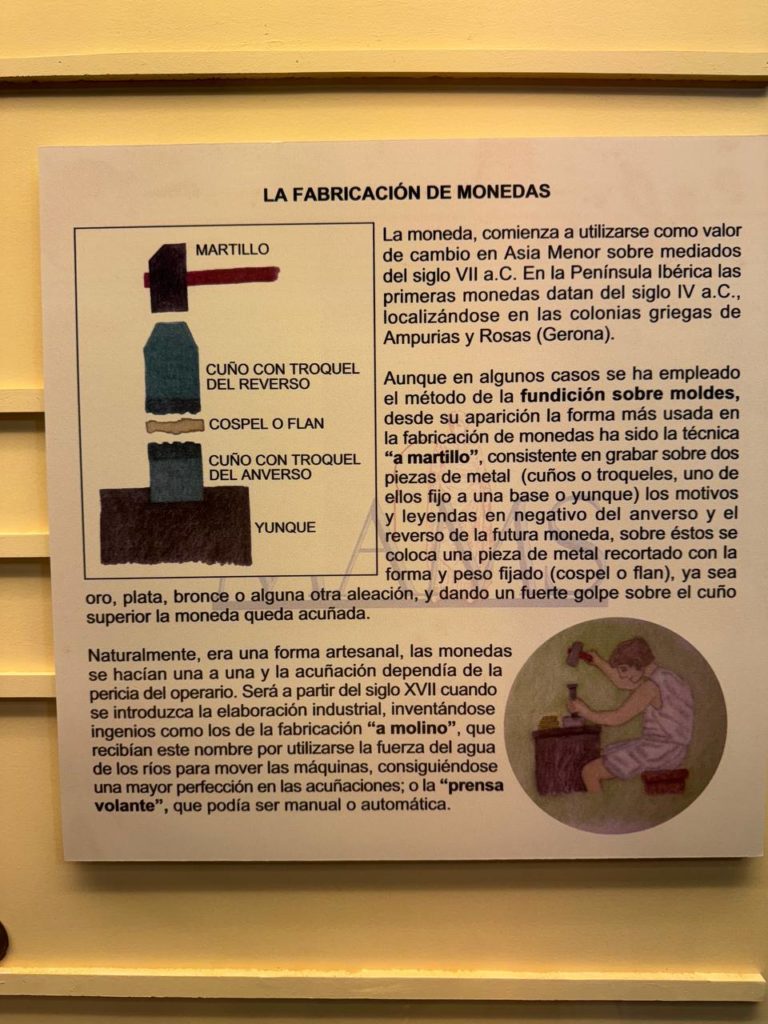

15. Coinage throughout history

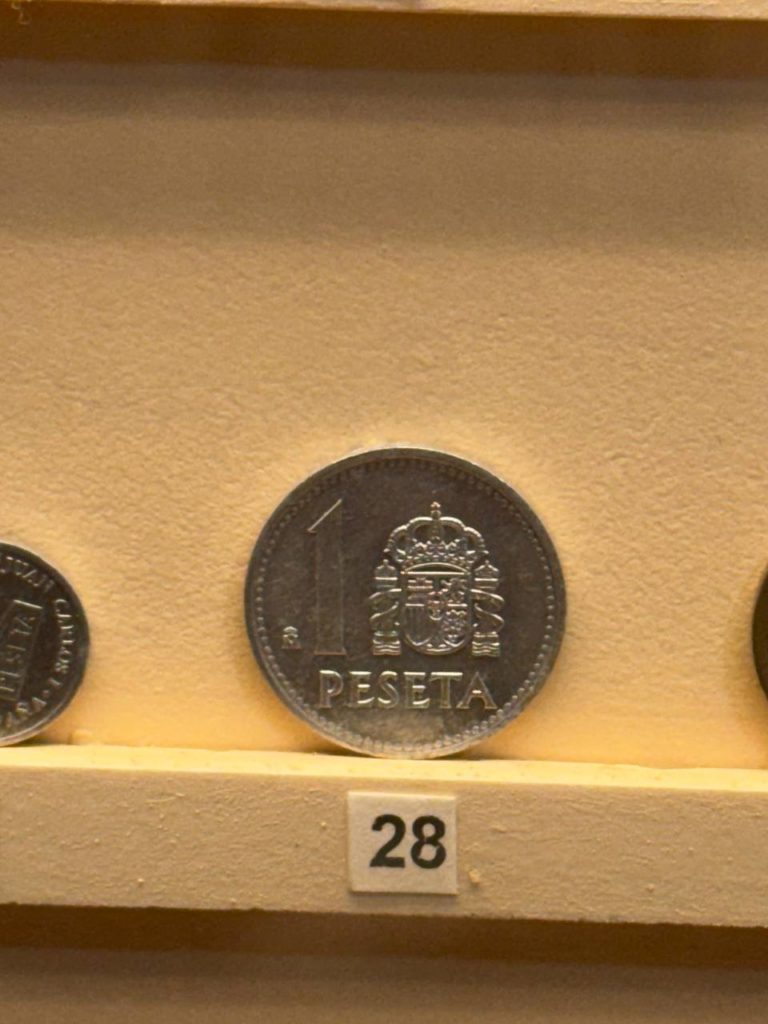

You have before you a journey through the different types of coins throughout the ages. Medina Sidonia minted coins with the name of the city in Phoenician characters around the 2nd and 1st centuries BC. It is followed by a representation of coins from different parts of Roman territory from the Republican period and from most of the emperors who ruled from the 1st century until the fall of the Western Roman Empire.

In the Visigothic period it again minted its own gold coinage, although no specimens have been found. The excavations have also yielded Islamic coins from al-Andalus in bronze and silver; from the different Christian kings of the late Middle Ages and the Modern Age, up to the reign of Juan Carlos I until the end of the 20th century.

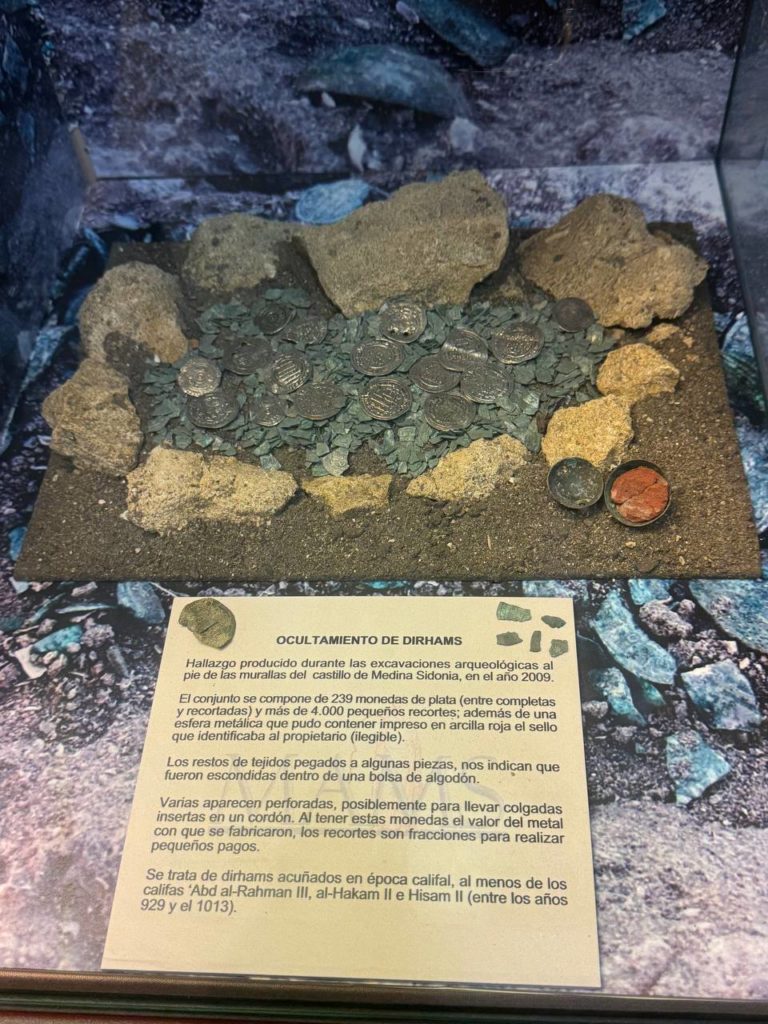

But perhaps the most striking feature of this display case is the two treasures on display. They recreate two discoveries made in the castle of Medina Sidonia during the archaeological excavations carried out in 2009.

The first of the concealments or treasure trove is that of Islamic dirhams minted in the Caliphate period, between the 10th and 11th centuries, which was found at the foot of the southwest wall of the fortress. The assemblage consists of more than 200 silver coins and several thousand small cut-outs (used at the time for small payments), as well as a metal sphere containing red clay, which may have been stamped with the name of the owner (now illegible). The remains of fabrics attached to some of the pieces indicate that they were hidden inside a cotton bag.

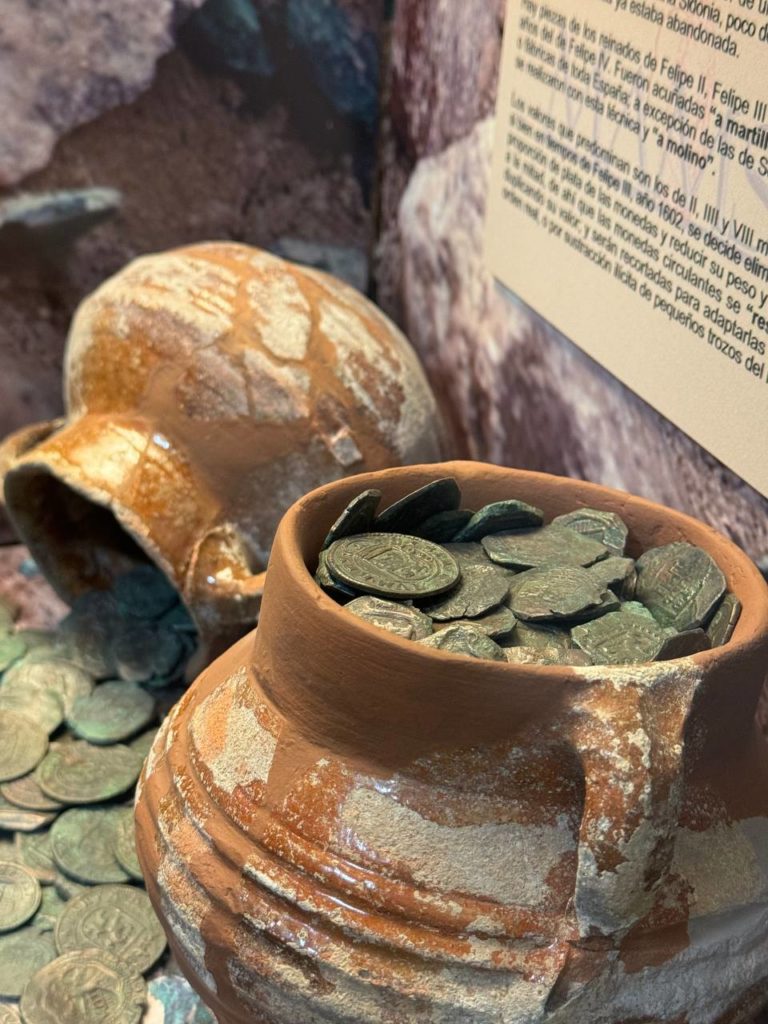

The treasure trove of maravedís is made up of a group of 828 fleece coins (bronze with silver alloy), which were hidden inside two small clay pots inside one of the cisterns of the 15th-century castle of Medina Sidonia, shortly after 1626 and when the fortress was already abandoned. The pieces belong to the reigns of Philip II, Philip III and the first six years of Philip IV.

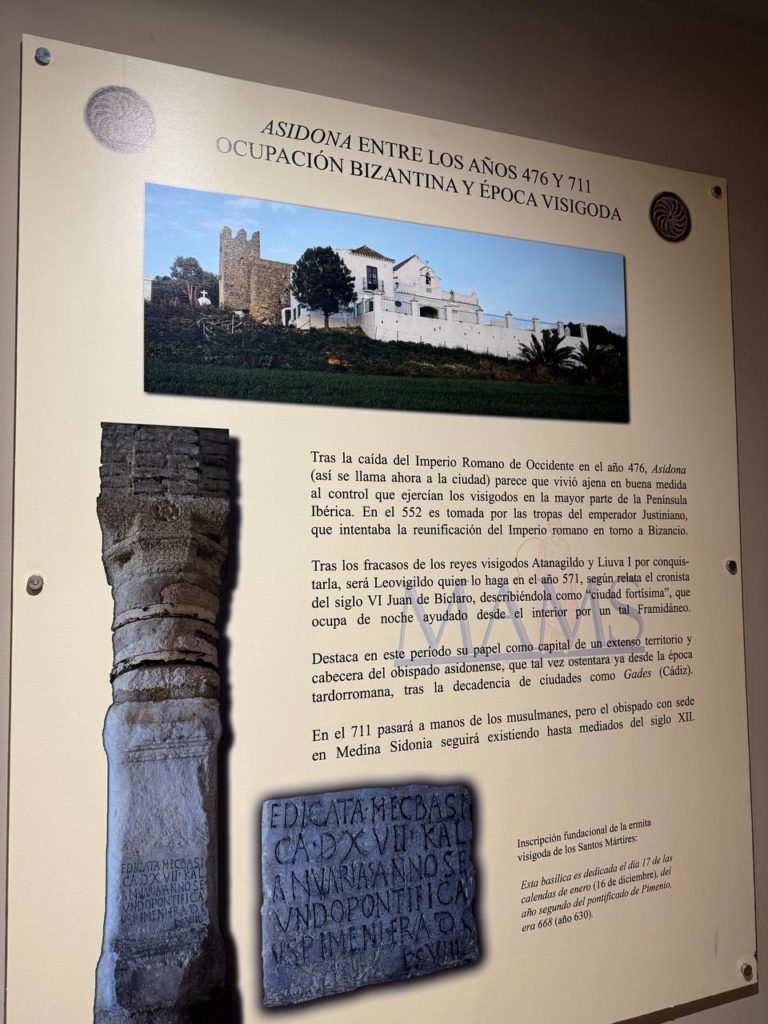

16. Byzantines and Visigoths

Asidona was occupied by Byzantines and Visigoths between 476 and 711. During this period it was the capital of an extensive territory and the head of the bishopric of Asidon, which it may have held since late Roman times, following the decline of cities such as Gades (Cadiz).

In 711 it fell into the hands of the Muslims, but the bishopric with its seat in Medina Sidonia continued to exist until the mid-12th century.

Among the objects on display from this period, we can highlight a Visigothic cancel of unknown provenance; it is a piece with Christian religious symbols in relief, which was placed inside the church, in front of the altar, separating the sacred space from the faithful.

This one, in particular, has a peculiarity: the stonemason who worked on it copied it from a mould, but he knows that the moulds are made in negative, so that when the imprint is made, it remains in positive. The stonemason copied it as it was and the image appears with the symbols upside down.

The exhibition of this period is completed by some inscriptions and a display case with everyday items and ornaments for personal use.

17. Showcase from the Muslim period

This is the display case containing various remains from the Muslim period.

From the entry of the Muslims in 711 until Alfonso X conquered the territory in 1264, it was known as Madinat Saduna.

It maintained the territorial pre-eminence it had already enjoyed under the Visigoths, being the capital of the core of Saduna, a district that extended beyond the limits of the present-day province of Cádiz.

Among the objects on display from this period are candlesticks, with the same function as Roman lanterns. Saddlers’ thimbles, so important for sewing leather, of which they were great saddlers.

Knife handles, various ceramics, some of which were produced in the Almohad-period ovens located beneath these rooms of the museum, etc.

18. Showcase of the border

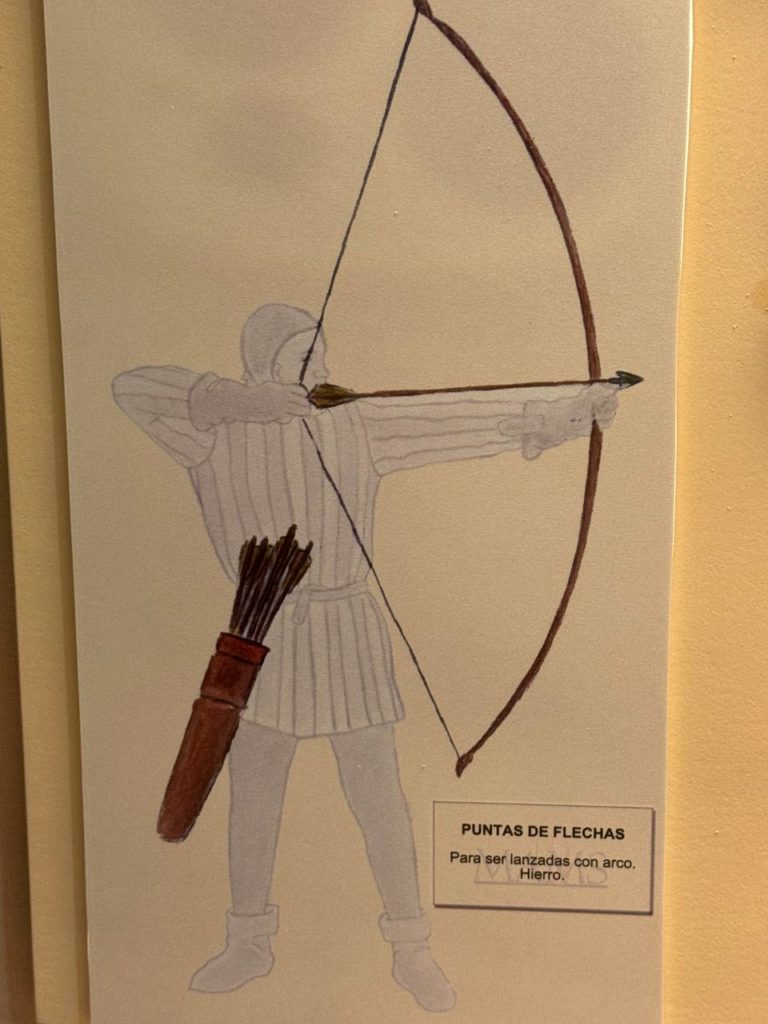

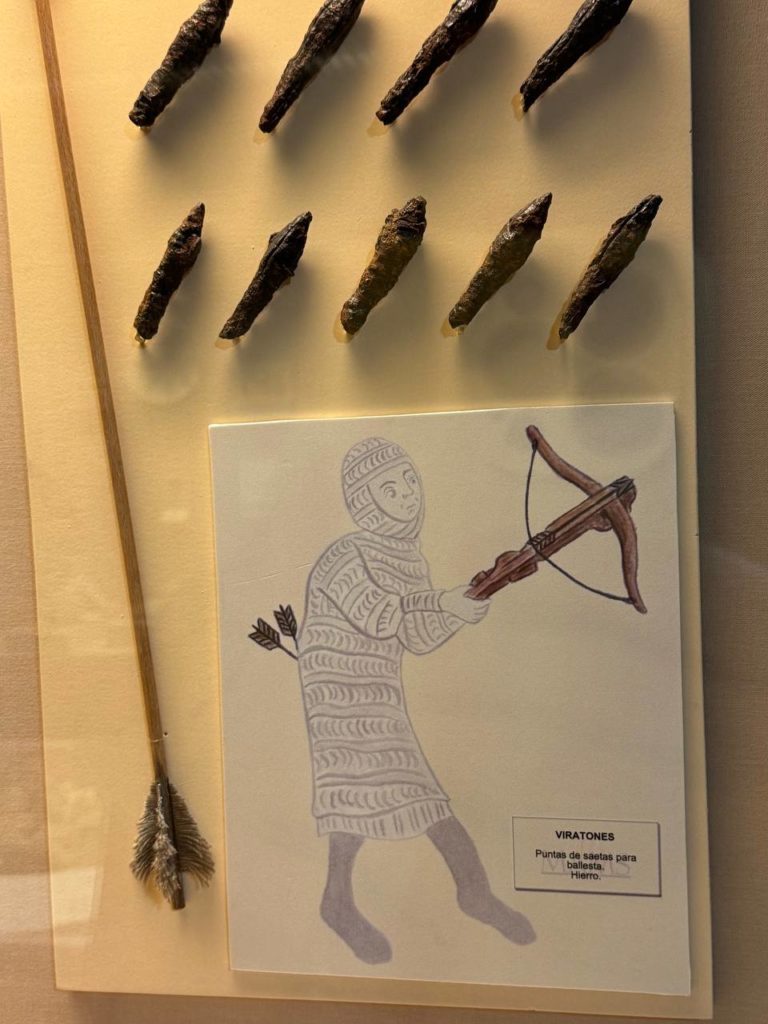

Alfonso X conquered Medina Sidonia in 1264, and from that date it remained in the Castilian crown, but the Muslim raids, as the border with the kingdom of Granada was so close, meant that life was not comfortable in this part of the peninsula, although there were moments of full coexistence between the two cultures, with peaceful commercial exchanges.

That is why we have so many towns with the surname of the border, such as Jerez de la Frontera, Conil de la Frontera, Vejer de la Frontera, etc… Even Medina Sidonia was also given this name, because to compensate for the danger, the crown granted some benefits to these border towns.

Thus, the frontier was in constant instability and it was necessary to be prepared to defend oneself; proof of this are the iron arrows and other projectiles or stone balls that are exhibited in this display case.

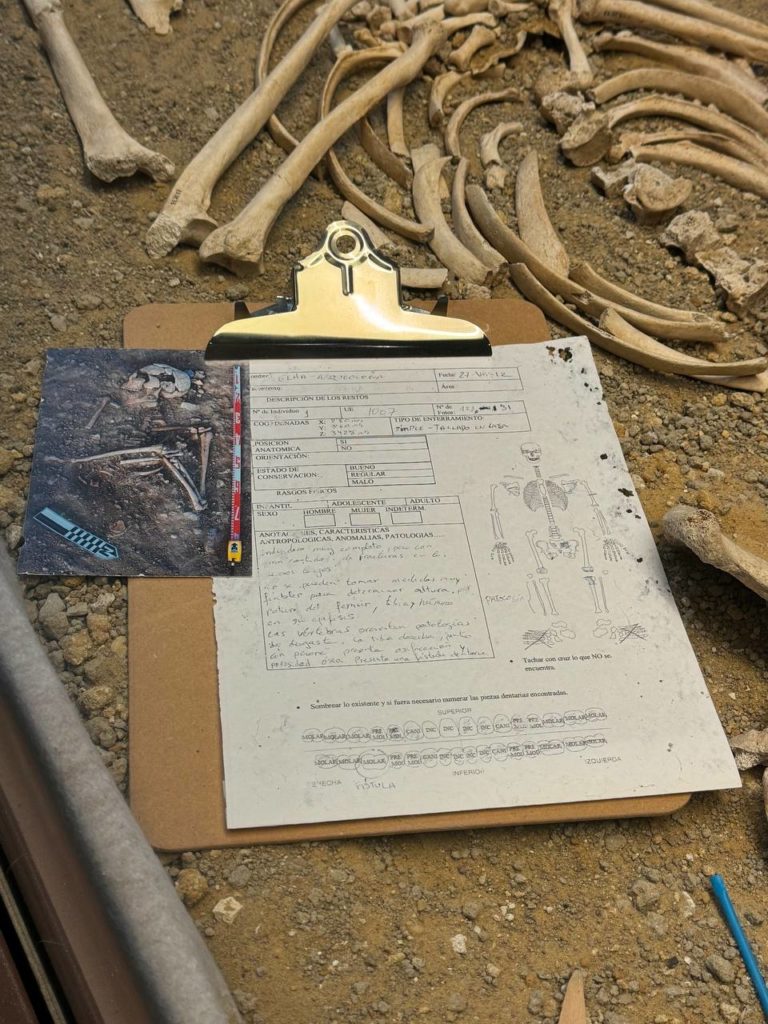

19. Showcase with the skeleton

This is the body of a possible warrior from the medieval period, buried with other bodies next to the remains of a church located at the entrance to the castle and dedicated to St. James the Apostle.

The small nails that can be seen around the body are evidence that it was buried in a coffin, although the wood has disappeared over the years. The objects that accompany the body are a recreation of the archaeologist’s work, brush, trowel, scale, tablet for taking data, etc.

If you look at the teeth and their state of preservation, you will realize that this is a relatively young individual, although he has an impacted tooth that must have caused him a lot of pain.

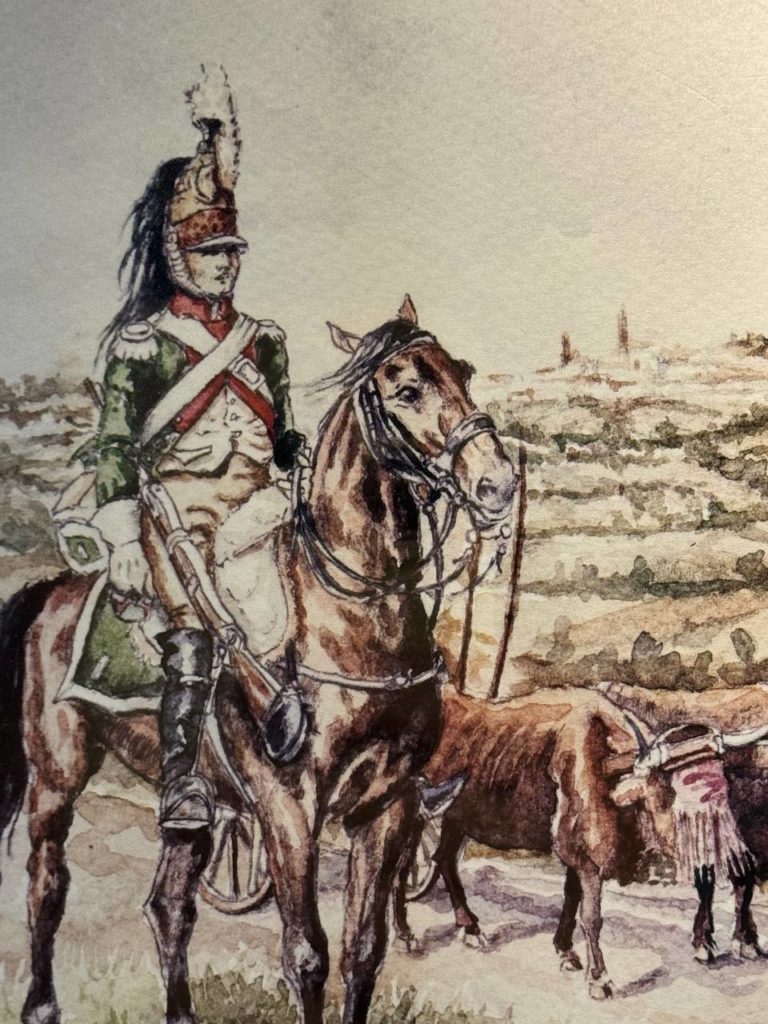

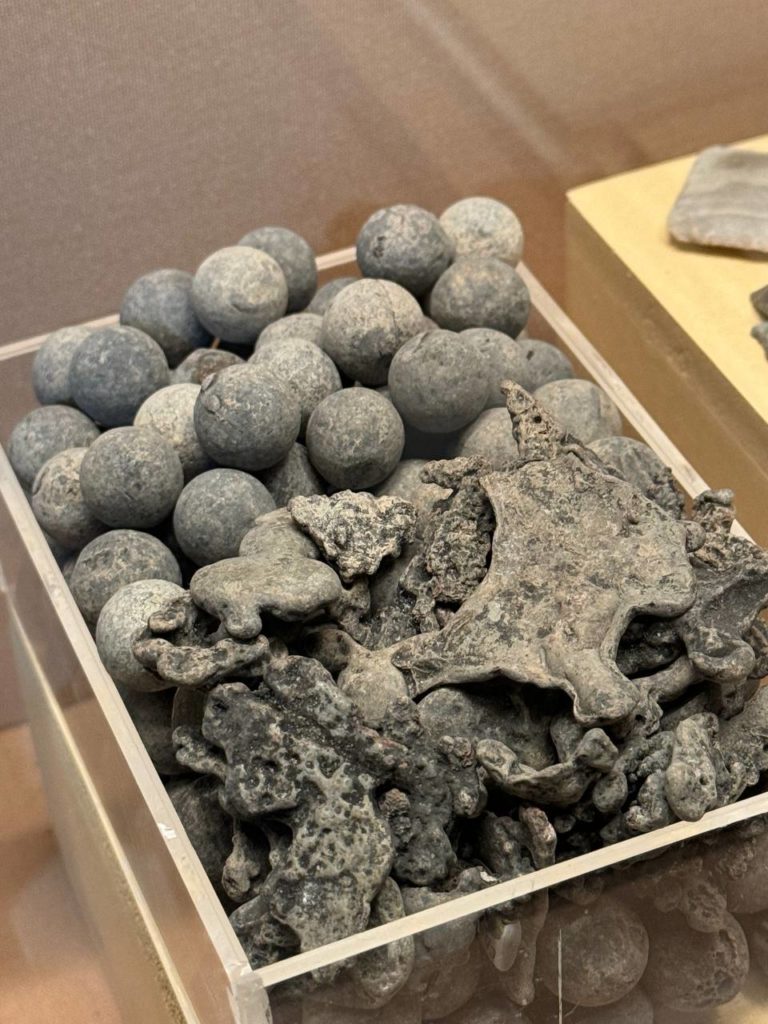

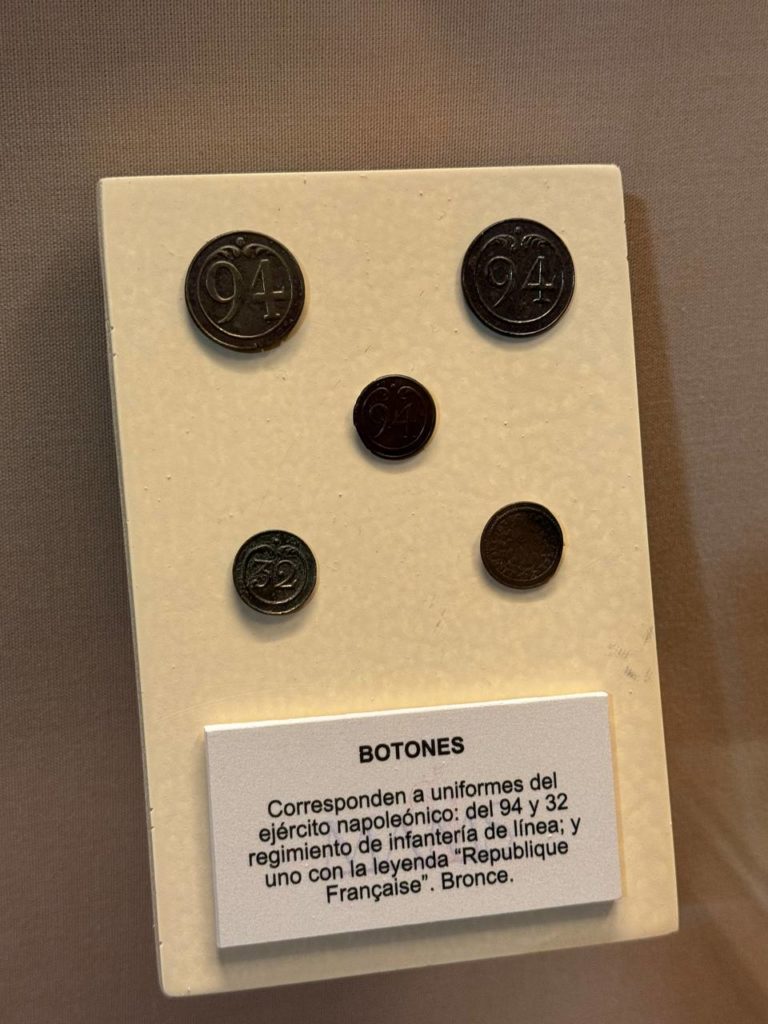

20. Showcase of the Napoleonic period and local ceramics.

During the War of Independence, the French had a military garrison in the castle of Medina Sidonia. They rebuilt parts of the fortress by erecting some walls and building barracks and other outbuildings for the troops. Once they had withdrawn in August 1812, the Spanish Regency ordered everything built to be demolished, in case the invading army returned.

From their time here you can see the buttons of the warriors, a compass with the Fleur de Lis, the emblem of the Bourbon monarchy (this piece could well be Spanish), ceramic pipes, rifle bullets, among other objects.

Finally, the museum closes with an exhibition of pottery from Assidon. It was very famous at least from the 18th century until the middle of the 20th century, because of how well it distributed and maintained the heat of the fire and the flavour that the earthenware gave to the stews.

Today, unfortunately, there is no one to continue the potter’s trade in the town.

And with these famous pots from another recent era, we conclude our tour through our history, hoping that you have enjoyed it and that you will come back to visit us soon.