1. Introduction

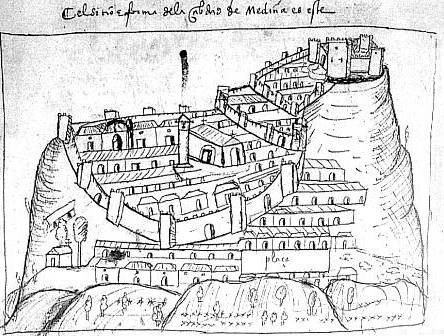

Welcome to the archaeological remains of the “Cerro del Castillo”, located in the highest area of Medina Sidonia, almost 337 meters above sea level.

Archaeological excavations began here in 2004, under the direction of the archaeologists Manuel and Salvador Montañés Caballero, revealing the structures of three different fortifications, one from the Roman period, another Islamic, and a third from the Christian period at the end of the Middle Ages; and also bringing to light traces of two moments of reuse: for the settlement of the Napoleonic troops and in the 20th century when the land was acquired by a private individual.

Thus, during the visit, you will be able to observe different structures, construction techniques, curiosities and historical facts, as well as enjoy landscapes of great natural beauty thanks to the strategic and privileged location of this archaeological site.

2. The Roman military Castellum

The first building line corresponds to the Roman Castellum, dated between the 2nd and 1st centuries BC.

When the Carthaginians were defeated in 206 BC, the Romans continued to occupy this hill, as it was an enclave of great strategic value due to the control from here over a large part of the coast and the mountains of what is now the province of Cadiz.

A new city was founded on its slopes in the time of Emperor Augustus, keeping the Phoenician-Turdetan name of the previous one: Asido, to which was added Caesarina, in memory of Julius Caesar, who may have been one of its benefactors.

The construction of the military fortress occupied one hectare of land, and its defenses included a moat dug in the natural terrain, more than 7 m deep and wide, and walls with tower counterforts on the main sides.

The material used in the construction of this castellum was large sandstone ashlars, some of them very large, which formed the outer faces of the walls, while the inside was filled with the typical opus caementicium, a mortar of lime and tough stones, walls which, with varying degrees of preservation, can be seen in different parts of the site.

The castellum could house a garrison of about a hundred soldiers.

As well as being a defensive structure, during the final years of the Republic and the High Empire, when the territory was at peace, it became an element of propaganda and a symbol of the power of Rome.

Later, until the 9th or 10th century, during the Muslim Caliphate, when it was demolished, it recovered its role as an almost impregnable military defense.

3. Concealment of coins

In the different campaigns of archaeological excavations carried out in the Castle, coins from the different cultures that have occupied this height have been found individually, spanning more than two thousand years, from the 2nd century BC to the reign of Juan Carlos I.

Two coin caches (popularly known as ‘treasure troves’) have also been found, corresponding to two different periods: one Islamic, in the upper part of this silo and made up of more than 200 silver coins, called dirhams, minted in Medina Azahara and other cities of the Caliphate of Cordoba, between the 10th and 11th centuries, which were once kept in a small cloth sack.

Another hiding place inside one of the cisterns in the upper part of the castle, made up of 828 bronze coins, maravedis which were deposited inside two small jars and date from the end of the 16th century to the middle of the 17th century.

Different versions could be given to explain these concealments or treasures, but in our case, the Islamic coins could have been hidden at a time of political instability or war in the territory, while the maravedís could have been hidden in the ruins of the castle after an illegal appropriation. In either case, the person who hid the coins could not recover them and so they have come down to us.

Both sets of coins are currently on display in the Archaeological Museum of Medina Sidonia.

4. The castle in the late Middle Ages

After the definitive conquest by King Alfonso the tenth the Wise and the expulsion of the Muslims from the Cora of Sidonia in 1264, the Christians established their cultural and religious dominion, castilianising the name that the town had in Islamic times, and renaming it Medina Sidonia.

Due to the small population of the town of Asidon, the castle and the other fortifications on the top of the hill and the walls of the town deteriorated. For this reason, there were continual requests from the villagers for the king to help them repair the walls, as the border with the kingdom of Granada was very close.

In 1440, the House of Guzmanes was given the seigniory of Medina Sidonia and its surrounding area to the House of Guzmanes, and in 1445 the duchy of Medina Sidonia was created, which bore the same name as the town.

This will give a boost both in the increase in the number of inhabitants and in the repair of the defenses and, especially, with the construction of a new castle by the II Duke, which will be attached to the almost demolished castle from the Muslim period.

The castle was built with thick stone masonry walls and ashlars, with the addition of technical innovations after the advent of gunpowder, such as gun ports and the reinforcement of the lower part of the perimeter walls with a slope.

To obtain the necessary means for these great defense works, the ducal house would allocate the money from some taxes and fines to these works; and would also ask for the favor of the church, such as the Bull granted by Pope Nicholas V, granting forgiveness for their sins and the liberation of the ill-gotten goods of the last ten years to the faithful who helped with their work or financially.

This new castle would begin to be dismantled from the 17th century onwards and its materials reused in buildings in the town, both public and private (the main church and the town hall were built partly with stones taken from the castle), with a few ruined walls of this fortress being the only ones that came out of the ground before archaeological work began in 2004.

5. The Islamic castle

With slight variations, reinforcements, and reconstructions during the period of Byzantine occupation and the Visigothic reign, and the first decades of the Muslim presence on the peninsula, the Roman castellum remained standing, but around the ninth or tenth century, it was largely demolished as a measure of punishment against the inhabitants of Medina Sidonia.

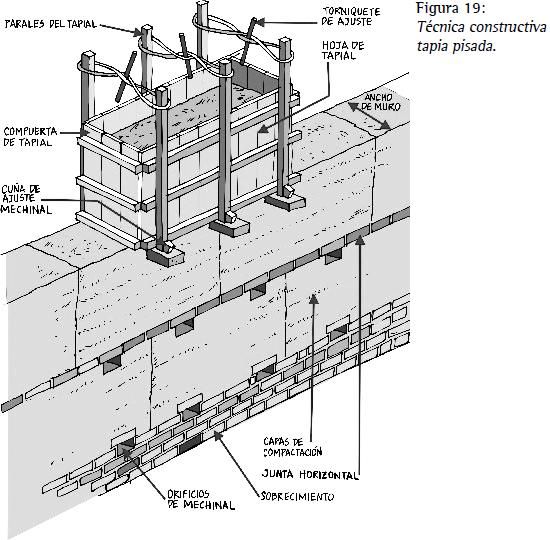

It was not until about a century later that another fortress was built on the same site, in this case using the technique brought by its North African builders, the Almoravids and the Almohads.

This Islamic-period wall is characterized by the use of rammed earth, a construction technique that employed a wooden formwork or box that was filled with earth and some lime that was tamped down, and when it hardened, the boards were removed and another box was built on top or next to it and filled in, until the desired height and length of the wall was reached.

During the first centuries of the Islamic period, Medina Sidonia was the capital of a large Muslim territory or province, known as the Cora of Sidonia (as it had previously been the capital of the county of Asidona in the Visigothic period and the seat of the bishopric of the same name).

6. The castle in French times, to the present day

Napoleonic troops entered and established themselves in Medina Sidonia in February 1810, during the Spanish War of Independence, and as a rearguard for the French armies that had laid siege to Cadiz and the Isle of León.

For tactical and defensive reasons, in April 1811 they decided to establish a stable barracks at the top of Castle Hill, making use of the visible ruins of the medieval fortress, raising the perimeter walls, building barracks for the troops and rooms for officers, as well as other rooms such as stables and kitchens, as archaeological excavations have brought to light.

In August 1812, the French left the city in haste and the Spanish commanders ordered the destruction of all the buildings in the castle so that it would not be reoccupied, and from then on it fell into disrepair.

But still in 1925, after a private individual bought the land from the town council, it experienced a few years of new vitality, with walls and rooms being rebuilt, although without respecting what this fortress had originally been, and again in the thirties of the 20th century it once again became an abandoned site, but without ever ceasing to be an important point of reference in the history of Medina Sidonia.

Now in the twenty-first century, and thanks to the archaeologists Manuel and Salvador Montañés, who designed and directed the different archaeological excavation campaigns carried out to date, the impetus of the Town Council, and the financial support of the different administrations, this important and complex legacy of our past has been recovered for the enjoyment and knowledge of all.

7. Landscape from the castle

The main reason for keeping in the same place the different fortifications or castles that the summit of this hill has housed throughout history has been its magnificent location.

From the highest point, where our geodesic vertex is located at an altitude of almost 337 meters, the highest point in the Janda region, we can see the Jerez countryside and the city of Jerez, known for its magnificent wines and Carthusian horses.

To the northwest, El Puerto de Santa María and Puerto Real belong to the bay of Cádiz, with the natural park of Los Toruños standing out for its environmental value and marshes.

To the west, Cádiz with its impressive bridge, the longest in Spain, popularly known as the La Pepa bridge in honor of the first Spanish Constitution that was signed in Cádiz in 1812.

Next, the municipalities of San Fernando and Chiclana de la Frontera, and between these cities, landscapes of marshes and old salt marshes.

To the southwest, we find the municipalities of Conil and Vejer de la Frontera, and although out of sight, Barbate and Zahara de los Atunes, which make up the territory of the Janda Litoral, where its beaches and almadrabas, the fishing gear used to catch bluefin tuna, stand out.

On the same plane, but inland, the countryside of Benalup-Casas Viejas and the districts of San José de Malcocinado and Los Badalejos.

To the southeast, the fields of Tarifa can be seen and, on clear days, we can make out the coast of Morocco on the other side of the Strait of Gibraltar.

Beyond Los Barrios, our Alcornocales Natural Park stands out.

To the east, Alcalá de los Gazules and Paterna de Rivera, belonging to the inland Janda, where we can see our fighting bulls and the Retinta cow.

Finally, if we look to the northeast, we will find the Grazalema massif and the rest of the Sierra de Cádiz, and the plain of San José del Valle.

From this area and when there is a sufficient easterly wind blowing, we can see the flight of the griffon vultures arriving from the Alcornocales, or with a planned flight, the lesser kestrels, ready to hunt to feed their young.